Transitioning Existing Traffic Engineering, Transportation Planning, and ITS Positions

Transportation agencies, especially state DOTs, have been historically organized to expand and deliver infrastructure capacity. As society begins to place more value on system performance and reliability, the use of technology to better manage the existing infrastructure and share information quickly has become more important. Over the past decade, transportation agencies have advanced different approaches to organizing and creating a program structure for TSMO to effectively manage and operate the transportation system. For example, research conducted under the second Strategic Highway Research Program (SHRP2) in the Reliability focus area played a pivotal role in the concept of TSMO program planning by examining both technical and organizational support needed to enhance highway operations and travel time reliability at State DOTs and metropolitan planning organizations (MPOs). The research developed a capability maturity model (CMM) consisting of six key dimensions to help transportation agencies improve the effectiveness of their TSMO activities. The CMM specifically included organization and workforce in terms of organizational structure, staff development, and recruitment and retention. This and other efforts have enabled DOTs to slowly adopt and transition more positions related to management and operations of the transportation system (Grant, et al. 2017). The table below provides a description of traditional positions and includes suggestions for future incremental evolution to support TSMO.

Evolution of Existing Traffic Engineering, Transportation Planning and ITS Positions

|

Job Title |

General Summary of Position |

Future Roles and Responsibilities |

|---|---|---|

|

Traffic Engineer |

Position is primarily responsible for applying principles and practices from civil engineering for the traffic operations of roads, streets, highways, and their networks to achieve a safe, efficient, and convenient movement of people and goods. This position is also responsible for traffic operations studies, such as safety studies, intersection operations studies, traffic impact studies, interstate operation studies, interchange modification report, traffic signal timing studies, and signal warrant studies. |

|

|

Traffic Signal Engineer |

Position is responsible for all aspects of traffic signals, from design to operation. The successful candidate will have extensive experience in the field of traffic signal design, implementation, maintenance, and operations. This position may also be responsible for operating the Traffic Management Center and coordinating the activities of assigned staff to respond to citizens’ complaints regarding traffic signal issues. This position is also responsible for emergency traffic signal operations within the region. |

|

|

Freeway Operations Engineer |

Position is primarily responsible for development, evaluation, and deployment of new technology related to traffic engineering and ITS along the freeway system. This position is also responsible for overseeing and monitoring the continued deployment and enhancement of incident management, and other active traffic management techniques with an emphasis on system efficiency, cost effectiveness, and community acceptance. |

|

|

Arterial Operations Engineer |

Position is primarily responsible for development, evaluation and deployment of new technology related to traffic engineering and ITS along the arterial network. The successful candidate will provide liaison with other governmental agencies and the public for coordination of active arterial management projects/programs in the region. This position is also responsible for performing field observations of traffic conditions to validate concerns or inquiries and evaluate/make recommendations relating to the application of new technology to support the agency’s vision and mission. |

|

|

ITS Design Engineer |

Position is primarily responsible for the design of ITS projects. The successful candidate will prepare project plans and specifications related to ITS elements such as fiber optic cable systems, Closed Circuit Television (CCTV) cameras, Microwave Vehicle Detection System (MVDS), Dynamic Message Signs (DMS), etc., while applying the systems engineering process. |

|

|

ITS Planner |

Position is responsible for planning and developing ITS projects, including preparing documents that follow the Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) systems engineering process. The successful candidate will be responsible for completing transportation planning and feasibility studies for DOTs, MPOs, and local municipalities. |

|

|

Transportation Planner |

Position is responsible for long-range transportation planning and considering safety, environmental, and efficiency issues in areas such as land use, infrastructure analysis, environmental compliance, and corridor planning. This position allocates resources to initiate and develop projects, and is responsible for the identification of needs, the preparation of plans and estimates, and adherence to regulations. |

|

Eventually, the positions in Table 2 will need to evolve for DOTs and other transportation organizations to adjust to the changing environment enabled by evolving technologies.

Emerging TSMO Positions in DOT and Other Agencies

The research conducted to develop this guidebook identified a set of emerging professional-level positions that should be considered by DOTs and many of the consultants they hire in the evolution of the TSMO workforce. These 19 positions were identified based on stakeholder feedback, literature review, and workforce research and reflect conversations around TSMO needs, emerging technologies, and broad workforce projections. Developing these positions within TSMO will move transportation agencies toward innovation and adaptability and create an opportunity to develop successful, highly effective, and state-of-the-art TSMO programs. The emerging TSMO positions include:

How to Integrate TMSO into DOT Business Practices

There is no one size fits all approach for organizing a DOT. While traditional units or divisions, such as a construction division, are commonly found across DOT organizational structures, the design of these organizational structures varies from state to state. Additional considerations about an agency’s organization structure include how resources are allocated (e.g., centralized vs. decentralized) and by whom work activities are typically performed (e.g., in-house vs. outsourced).

This range in designs makes it difficult to prescribe how to integrate a TSMO program into a DOT’s organizational structure. Focusing on common business practices within a DOT highlights several activities performed by all DOTs, regardless of organizational structure. Table 3 highlights the relationships between the 19 emerging TSMO position descriptions identified in this research and 9 common business areas within DOTs. Most of the 19 TSMO-related positions are expected to have significant roles in activities related to traffic and safety, TSMO, and research. Management-level positions (e.g., TSMO Program Manager) are expected to have involvement cutting across all major business areas.

As a DOT is beginning to develop its TSMO program, it is likely that TSMO-related positions will exist in the divisions or units that align with their role (e.g., a Traffic Data Scientist/Statistician may be found in the traffic and safety unit or operations unit). Because many of the TSMO program functions are crosscutting, these functions could be conducted in various DOT divisions or units.

As TSMO programs evolve, the DOT may consider consolidating the TSMO-related roles into a standalone TSMO unit. Having a standalone TSMO unit could allow the DOT to better define processes and workflows that cross traditional DOT business areas, which will increase efficiencies of the program.

Guidance for Hiring Specific TSMO Positions

Developing a Recruitment Plan

Most DOTs have long established processes that may need to be modified to reflect the nature of some of the emerging positions. It is suggested that a formal recruitment plan be developed for each new TSMO position that considers:

- When to recruit

- Where to recruit (traditional and non-traditional, internal to the agency or open, union vs.non-union)

- Use of recruitment specialist

- Screening and interview process

- Incentives

In addition, the emerging use of e-portfolio resumes and electronic resume screening should be considered, especially for positions that are recruited out of technology-based industries. These considerations and the recruitment plan in general should be done in cooperation with human resources (HR) staff to address potential changes in hiring policies and processes.

Determining When to Recruit

One of the greatest workforce challenges DOTs are experiencing may be identifying KSAs and positions they cannot currently foresee or envision. If an agency cannot foresee the need for a position, they will not be able to understand when to begin to recruit for a position. This foresight requires a broad understanding of current and future TSMO staffing needs, adapting current positions to incorporate new KSAs and creating new positions. It may be appropriate in some situations to evolve positions from their current focus and in others to add new positions with different KSAs. New positions should be considered in areas not easily addressed within the current DOT workforce and in circumstances that may trigger the need for new positions. Examples of such triggers might include the decision to formalize a new program, such as traffic incident management, or implement decision support software in a traffic management center. Triggers may also be externally activated through the emergence of technology in the private sector, such as connected and automated vehicles or mobility on-demand applications, or in response to cyber threats and malware attacks. This guidebook helps identify and provide example triggers for hiring new positions; however, to be effective it is important that someone within the transportation agency be responsible for monitoring these triggers and acting as appropriate.

The TSMO CMM framework can also be used to help identify when agencies are ready to develop or hire new positions. Shown in the table below, the TSMO CMM capability maturity dimensions and levels can be used to quickly self-assess the current capabilities of an agency, as well as determine where an agency strives to achieve. While an agency’s level will likely differ depending on the dimension, for this guide an agency’s overarching CMM level is the level with which most of their dimensions align. For example, if an agency’s self-evaluation found one dimension as a level 3, one dimension as a level 1, and the remaining dimensions as a level 2, that agency should consider their overall CMM level a 2. This CMM structure is used to identify triggers that can help an agency understand when it is time to begin recruitment for a new position.

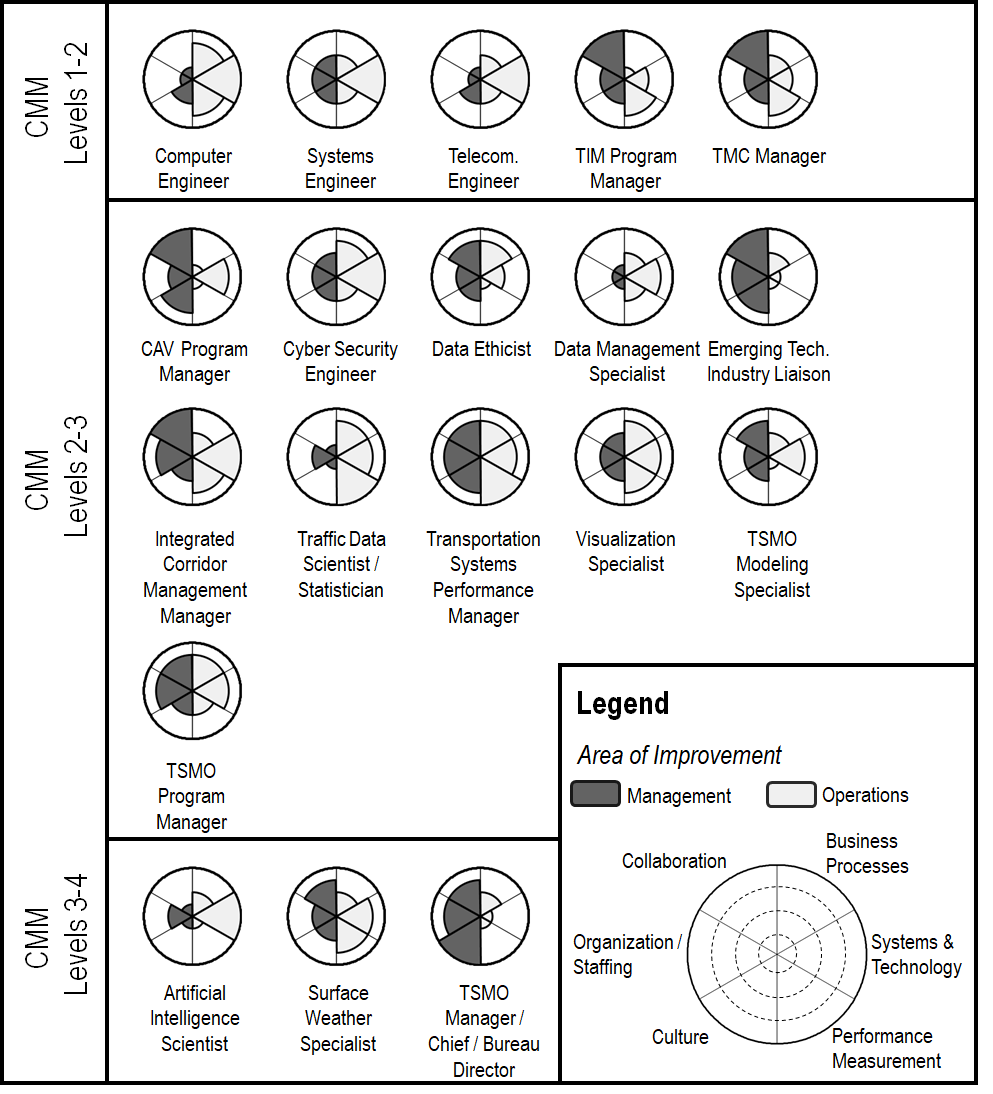

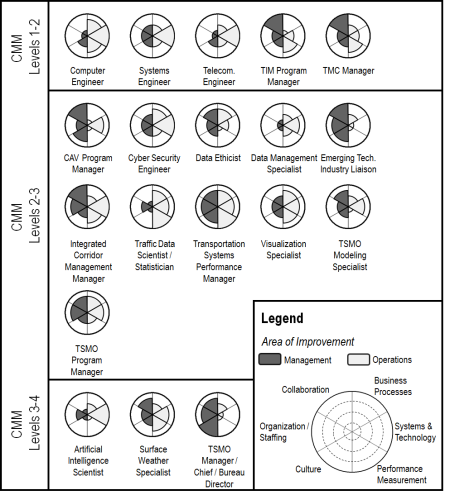

Figure 1 organizes the 19 emerging TSMO positions presented in this guidebook into three groups of CMM levels, and a detailed example of how to use this figure follows. These groupings do not indicate that all of the job positions in a single grouping must be present within a TSMO program before the program can move on to the next CMM level; rather, these groupings show common job positions found at the different CMM levels. A chart is included for each job position that shows the improvement potential for each of the six CMM dimensions. The more filled the chart’s dimension, the greater potential for improvement the job position adds to the dimension.

Figure 1. TSMO Job Positions and CMM Improvement Potential per CMM Level

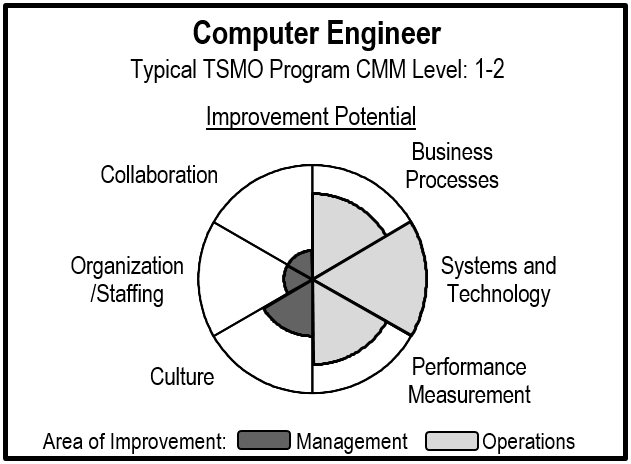

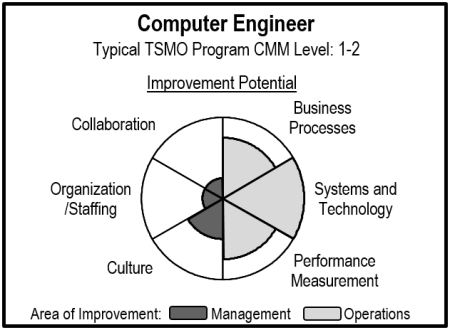

To help understand the information presented in Figure 1, Figure 2 is provided as an example focusing on a single job position (Computer Engineer). Both figures illustrate at what level of maturity the job position is typically found at the transportation agency. Using the Computer Engineer as an example, this job position is typically found in TSMO programs with a CMM level of 1 or a 2. Next, each figure lists six areas of improvement (e.g., business processes) and describes the significance of the improvement when hiring the job position. These six areas are arranged in a circle, with the three areas on the left of the circle representing management, and those on the right representing operations.

As shown by the dotted concentric circles in the legend of Figure 1, a higher rating (i.e., more area filled in) represents a job position providing higher potential benefit to that area of improvement. Using the Computer Engineer example in Figure 2, hiring a Computer Engineer will have the highest potential for improving the agency’s systems and technology dimension, but a low potential for improving the agency’s collaboration or organization/staff dimensions. Looking at the distribution of the improvement potential, one can see that overall a Computer Engineer is expected to have a higher improvement potential on operations than on management, and this is shown by those areas shaded of improvement on the right side of the circle are larger than those on the left side of the circle.

Figure 2. The Improvement Potential at a DOT When Hiring a Computer Engineer

Determining Where to Recruit

Traditional DOT positions are generally recruited from within the agency, the transportation industry or civil engineering schools. A number of the emerging TSMO positions, such as Artificial Intelligence Scientist, Transportation Data Ethicist, and Emerging Technologies Industry Liaison, require specialized training and experience in areas not traditionally recruited by DOTs. Other positions require experience in areas that have traditionally been addressed in other departments or partner agencies, such as Computer Engineer or Traffic Incident Management Program Manager. The consideration of where to recruit can also take a geographic focus of internal to the agency, locally, regionally, and nationally. Some of the emerging positions may require a broader regional or national search to find the KSAs needed.

Considering the Use of Recruitment Specialists

In some instances, a third-party recruitment specialist may be needed to solicit potential candidates. Positions that may benefit from the use of a recruiter include the higher-level management positions, such as TSMO Manager/Chief/Bureau Director, or are highly specialized and unaware of the emerging need for their KSAs within transportation, such as Visualization Specialist or Artificial Intelligence Scientist. Recruitment specialists can be helpful in hiring in competitive markets, or in areas where the cost of living impacts the availability of candidates. Recruiters may cost the hiring agency 10-20 percent of the first year hiring salary for a position.

Developing the Screening and Interview Process

Standard DOT applicant screening generally checks to see if the applicant provides some level of verification for the level of education, the number of years of experience, required licensure or other certifications, and KSAs as noted in the job posting. Some of the emerging TSMO positions do not have equivalency in traditional transportation agencies, making it difficult for DOT HR personnel to readily identify examples of KSAs or experience that may be similar or parallel to those required in the posting. For example, a visualization specialist who has worked in manufacturing or public utility agencies may have skills that directly translate into the visualization of systems operations or traffic flows but may be so nontraditional to agency HR staff that they are not readily identified as meeting the posting requirements. It is important to develop a range of example KSAs for each position to be used in applicant screening.

Interview structure and questions face similar challenges to applicant screening and should be tailored to the specific job responsibilities and desired KSAs for the position. Examples of previous work may be requested for certain positions, such as sample products for Visualization Specialists or Traffic Data Scientist/ Statistician. These should be identified as part of the recruitment plan and requested of the applicant prior to the interview. Collaboration and communication skills are critical to a number of TSMO positions. Interviews should include interactive discussions, behavioral competency questions, scenarios or role-play exercises to determine candidates’ interpersonal and collaborative skills.

Determining Incentives

As a number of emerging TSMO positions do not currently exist in transportation agencies or exist in limited numbers, it may be difficult to attract top talent into the specialized areas without offering competitive incentives. Potential incentives tied to dollars may be limited in government agencies, but incentives such as salaries, bonuses, moving expenses, and other incentives should be considered appropriate to the talent the agency is trying to recruit. More pragmatic and realistic incentives might include training, professional organization involvement, flexible work schedule, office space, remote work options, and extended leave opportunities. For example, discussions with a consulting firm that provides services to DOTs revealed a dramatic increase in unpaid leave of absence requests from younger staff. Another important incentive, especially for more specialized jobs that do not fit in the traditional DOT career tracks, are defined opportunities for career advancement within the organization. Advancement opportunities are critical to employee retention.

Best Practices in TSMO Workforce Retention

Adopting a culture of workforce retention and developing a personalized retention plan for each employee will address career and personal needs to enhance job satisfaction and greater commitment to the organization. Personalized retention plans should address job responsibilities, how the position supports the agency mission, training and advancement opportunities, salary and benefits, work conditions (workspace, flex-time, etc.), and employee recognition. It should address the specific needs of the employee in a way that is consistent with agency policies.

Emerging TSMO positions are often recruited from outside the transportation, public agency arena, and it may be challenging to retain employees more familiar and comfortable with the practices in the emerging technology fields. Government agencies may be constrained by law and policy in terms of compensation and benefit packages, but often the only constraint to creating effective work environments for emerging TSMO professionals is tradition. The following is a list of retention strategies that should be considered across the organization and specifically for TSMO.

The best practices in TSMO workforce retention, discussed below, focus on three categories: training and professional development, HR benefits, and workplace culture.

The table below lists each of the best practices described below and highlights how the practice was identified (i.e., from the literature or from stakeholder interviews).

Best Practices for Retaining a TSMO Workforce

|

Best Practice |

Category |

Literature |

Interviews |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Enhance on-boarding processes |

Trainings and Professional Development |

X |

|

|

Offer ongoing professional development |

Trainings and Professional Development |

X |

X |

|

Offer mentorship programs and opportunities |

Trainings and Professional Development |

X |

|

|

Provide training, including cross-functional training |

Trainings and Professional Development |

X |

X |

|

Offer performance-based compensation |

Human Resource Benefits |

X |

|

|

Provide flexible work arrangements |

Human Resource Benefits |

X |

X |

|

Ensure employee recognition |

Human Resource Benefits |

X |

|

|

Provide regular and effective feedback |

Human Resource Benefits |

X |

|

|

Clearly articulate mission and vision |

Workplace Culture |

X |

|

|

Clearly define expectations and policies |

Workplace Culture |

X |

X |

|

Provide clear internal organization communication |

Workplace Culture |

X |

|

|

Ensure organizational integrity |

Workplace Culture |

X |

|

|

Host team celebration and events |

Workplace Culture |

X |

|

|

Increase diversity |

Workplace Culture |

X |

|

|

Provide leadership opportunities |

Workplace Culture |

X |

|

|

Promote and ensure workplace safety |

Workplace Culture |

X |

|

|

Support professional organization involvement |

Workplace Culture |

X |

|

|

Allow appropriate and creative office space |

Workplace Culture |

X |

|

|

Offer extended leave opportunities |

Workplace Culture |

X |

|

|

Define career path and advancement opportunities |

Workplace Culture |

X |

X |

Trainings and Professional Development

New Hires

Orientation is a one-time event that provides essential information and protocols for new hires. Onboarding is an ongoing process that helps new employees adapt to the organizational culture and become successful in their new position as quickly as possible. Onboarding may include training, mentoring, social events, and other supportive activities. Recently, private sector companies have recognized the importance of the on-boarding process and have refocused the activity around the employee experience and less around completing paperwork. DOTs need to evolve onboarding processes to remain competitive. Within TSMO, some states have used the on-boarding process to allow for a broad introduction to quickly be exposed to various activities such as the TMC, safety service patrols, traffic signal shop, etc.

Mentorship programs are an effective part of onboarding new employees and enabling more seasoned professionals to guide and support development of less experienced employees. Mentoring can be used to support professionals moving from more traditional transportation positions into emerging positions where on-the-job learning can be essential. In addition to in-house mentoring, professional organizations offer mentoring programs that can be used to provide mentoring in specialized TSMO areas. The Institute of Transportation Engineers (ITE), Women’s Transportation Seminar (WTS), and the Transportation Research Board (TRB) offer mentoring opportunities to members.

On-going Professional Development

Ongoing professional training may be a combination of internal and external training, and focus on technical, managerial, communication, regulatory, and other important aspects of the job. It may also include nontraditional training opportunities such as hackathons, consumer electronics shows, or events like the Electronic Entertainment Expo (E3) to bring technology applications from other industries into the transportation field.

Cross-functional training is one the most effective ways to develop and advance existing staff into new and emerging TSMO functions and positions. It can provide support to career advancement and be part of a formal career path for non-traditional employees looking to develop into higher managerial positions within the agency. An example cross-functional training strategy is to implement temporary assignments for staff (e.g., 90-day, by task, by project). This approach allows staff to get a firsthand experience at roles that they may not have been qualified for when going through the normal recruitment process. Cross-functional training often provides the individual with a different perspective and can help them see how different roles fit together and ultimately help improve efficiencies and coordination at the agency.

Human Resource Benefits

When considering employee compensation, it is important to remember that total compensation is the combination of both salary and other benefits, such as paid time off with separate sick leave, disability insurance, and a defined benefit pension. Increased flexibility in terms of options and pre-tax flexible spending accounts can allow employees to design a package that best meets their needs. While transportation agencies rarely have the ability to vary the package and the options to attract or retain specific positions, they can offer other benefits. Such benefits can include work location and schedule options or unpaid leave to be more competitive with the private sector. Transportation agencies should recognize the value of the benefits they offer (e.g., paid leave, pension) and articulate value of these benefits to attract potential employees.

Performance-based compensation ties compensation to specific performance goals and outcomes. It motivates employees to deliver high-level products and advance the organization’s mission and objectives. Pay-for-performance is generally more effective in the private sector than in government agencies due to budgeting restrictions and the motivations of public sector employees. However, there may be specific situations in which performance-based compensation and bonuses can be effective in transportation agencies for retaining the best talent.

Employee recognition can be a low-cost opportunity to retain TSMO talent by letting them know their contributions are valued. This can include awards, monthly recognition of projects or activities, thank you notes, celebration events, certificates of achievement, reserved parking, gift cards, and other visible perks or recognition.

Regular and effective feedback can motivate employees by reducing confusion and frustration and acknowledging accomplishments. It can also allow the employee to feel part of a larger effort and more engaged in the team.

Workplace Culture

There are a number of ways to improve the workplace culture to assist in retaining the workforce. This section lists several best practices and provides a brief overview of each.

- Clearly articulated mission and vision. Transportation agency employees often choose government employment with a strong sense of public service. Clearly articulating the TSMO mission and vision and how each employee contributes to them can build strong affinity to the agency and support retention.

- Clearly defined expectations and policies. A clear understanding of job expectations and agency policies is an important part of effective employee orientation and onboarding. These can be supported through ongoing training, regular employee feedback and mentoring.

- Internal organization communication. Internal communication supports a clearly articulated mission and vision, enhances an understanding of agency culture and policies, and encourages employees to feel part of the larger organization.

- Ensure organizational integrity. Organizational integrity is integral to employees feeling good about where they work. This is especially important to agency employees who are motivated by public service.

- Host team celebrations and events. Team celebrations and events build camaraderie, acknowledge successes, and reinforce positive outcomes.

- Increase diversity and inclusion. Workforce diversity and inclusion benefits organizations through enhanced creativity, innovation, collaboration, and a reputation as a good place to work. This can help not only in retaining but in recruiting talent.

- Provide leadership opportunities. Opportunities to lead teams, initiatives, or programs can motivate personal growth and skill development. Leadership opportunities can be an important part of a defined career path and advancement in an organization.

- Promote and ensure workplace safety. Providing a safe workplace is essential to employee retention. Workplace safety includes employee training and increases a sense of appreciation for the welfare of employees.

- Support professional organization involvement. Encouraging and supporting employee involvement in professional organizations enhances employee development through training opportunities, sharing information, and experience; and advancing the national TSMO dialogue can enhance motivation and commitment.

- Allow appropriate and creative office space. Office spaces that encourage collaboration or allow focused concentration are important to meeting the specific needs of employees and their job functions. Providing appropriate and creative office space can improve employee satisfaction and retention.

- Offer remote work options.Like flexible work schedules, the opportunity to work remotely can increase retention through improved work-life balance and flexibility.

- Offer extended leave opportunities. Despite limitations in most organizations on paid leave, unpaid or extended leave options allow employees the opportunity to pursue study, travel, and family activities. These can improve employees’ knowledge, perspective, and general morale.

Define career path and advancement opportunities. Defined career paths and advancement opportunities are important for employee retention. Articulating how an employee can move up in the organization encourages him/her to stay and grow with the agency. This may be particularly challenging for some of the more specialized, emerging TSMO positions, and can include cross-training and mentoring to provide needed KSAs for advancement.

Sample Workforce Development Plan

|

Basic Training |

Advanced Training |

|---|---|

|

New DOT Employee Orientation Duration: 1.5 hours Format: Webinar logged in DOT Knowledge Management System (KMS) Description: Provide a brief overview of TSMO at a very high level |

New TSMO Employee Orientation Duration: 24 hours Format: ½ Immersion and ½ self-guided tutorial Description: Immersion training including visits to TMC, Statewide Emergency Operations Center (EOC), Maintenance Garage, Safety Service Patrol ride along, Snow Removal ride along (as weather permits) and university partner. |

|

Co-Op/Intern Experience Duration: 8 hours Format: Lecture and site visits Description: ½ day lecture on TSMO and ½ visiting TMC and Safety Service Patrol |

|

|

TSMO 101 On-Line Training Duration: A series of about 6-30-minute modules that cover the basis of TSMO Format: Webinar with scored quizzes Description: Preliminary list of modules include: Introduction to TSMO, the role of the TMC, how TSMO impacts how we plan projects, how TSMO impact how we design projects, how TSMO impacts how we manage the transportation network |

TSMO 201 Advanced On-Line Training Duration: A series of about 12-30-minute modules on advanced TSMO topics Format: Webinar with scored quizzes Description: Example topics include: Work Zone Management, Traveler Information, ITS Field Device Design, ITS Maintenance, Planning for TSMO, ITS Data Management |

|

District Awareness Training Duration: 3.5 hours Format: Lecture Description: A series of 20-minute modules that provide an overview of DOT’s TSMO Program |

District TSMO Practitioner Training Duration: 8 hours Format: Lecture Description: Provide an overview of how District TSMO staff are expected to coordinate activities with Central Office including: budgeting, planning for operations, TSMO project Design, Traffic Incident Management, and Emergency Management |

|

Basic State DOT Operations Academy Duration: 2 days Format: Combination of lectures, group exercises, and at least one field visit Description: A series of one-hour lectures by different regional subject matter experts Modeled after National Operations Academy |

Advanced State DOT Operations Academy Duration: 4 days Format: Combination of lectures, group exercises, and at least one field visit Description: In-depth training on all aspects of TSMO including a presentation by national subject matter experts Modeled after National Operations Academy |

Additional HR Resources

While Industry Assessments aim to provide an overview of the current state of practice of the industry, below we've compiled resources specifically for HR professionals looking to expand their TSMO workforce. Specific resources in the NOCoE Knowledge Center include:

- Attracting, Recruiting, and Retaining Skilled Staff for Transportation System Operations and Management

- Training Programs, Processes, Policies, and Practices

- Developing Transportation Agency Leaders

- L17 SHRP 2 White Paper: What the Beginning Practitioner Needs (and other topics)

State DOT HR Resources

AASHTO runs a job board that features many job openings for state and local DOTs: https://jobs.transportation.org.

Additionally, the Southwest Transportation Workforce Center has provided the following links to state DOT and transit training programs, workforce development success stories, and other workforce program resources:

Arkansas

- Arkansas State Highway and Transportation Department Careers

- Arkansas Center for Training Transportation Professionals

- Arkansas LTAP

- Arkansas Transit Association Training Program

Florida

- FDOT Careers

- FDOT Internships

- FDOT Construction Training

- FDOT Transportation Development Training

- Entry-Level Transportation Construction Workforce Shortages - Report

- Florida LTAP

- Florida Transit Operator Training Program

Georgia

Kentucky

- Kentucky Transportation Cabinet Careers

- LADOTD Student Employment

- KTC Scholarship, Education, and Training Resources

- Kentucky LTAP

Louisiana

Mississippi

- MDOT Careers

- MDOT K-12 Outreach (AASHTO TRAC & RIDES)

- Mississippi LTAP

North Carolina

- NCDOT Certification and Training Program Listings

- NCDOT Careers

- NCDOT Workforce Success Stories - November 2010

- NCDOT Workforce Success Stories - April 2012

- NCDOT On-The-Job-Training Job Postings

- NCDOT Internship Network Programs

- NCDOT School to Career

- North Carolina LTAP

- Scott Logistics - Current Openings

Puerto Rico

South Carolina

- SCDOT Careers

- SCDOT Training

- Workforce Development Program for the SCDOT - Report

- South Carolina LTAP

Tennessee

- TDOT Careers

- TDOT Learning and Development

- TDOT Graduate Transportation Associates

- Tennessee LTAP

- Tennessee Transit Training Center (http://mtweb.mtsu.edu/tttc/about.htm)

- TN TransitJobs

Virginia

- VDOT Careers

- VDOT Career Development Pathways

- VDOT Training

- VDOT University Virtual Campus

- VDOT Business Opportunity and Workforce Development Center

- Virginia LTAP

- VA Transit Jobs

West Virginia

- WVDOT Career Opportunities

- WVDOT Transportation Engineering Technician Certification Program

- WVDOT Transit Training Opportunities

- WVDOT Workforce Development Study Report

- West Virginia LTAP

Local Technical Assistance Program/Tribal Technical Assistance Program Clearinghouse and Resources

NCHRP Report 865: Strategies to Attract and Retain a Capable Transportation Workforce

TCRP Report 77: Managing Transit's Workforce in the New Millennium